It’s often been said that in business one should strive to fail fast, fail safe, fail cheap and fail often. Well, failing is easy enough – all you need to do is create a bad product, or even create a good one and then fail to promote, sell and support it. However, I suspect that the “fail fast” mantra is supposed to be a snappier version of “try hard to succeed, expect to fail a lot but keep trying hard and make sure the failures are cheap and quickly identified so you can learn from them”.

I attended a great presentation recently by the CTO of PARC who spoke about creating a culture of allowing experimentation without the stigma that comes from failure. He emphasized the need for clear measurements on experiments, so we can identify why something failed, learn from it and “make better experiments tomorrow”. He went on to offer examples of PARC projects that had failed initially but, after repeated experimentation, yielded valuable and innovative products. I thought I would share some of my own favorite stories of amazing success plucked from the jaws of repeated failed attempts.

1) The Wright brothers

The Wright brothers are the greatest example of enthusiastic amateurs achieving their goals where professional experts had failed. They started building gliders in 1899 using the best information available to them but by 1901 Wilbur was so disillusioned with their efforts that he told his brother that no person would fly for 50 years. They might have given up completely at that point, but they had shared their experiments with Octave Chanute and he encouraged them to present their findings in a lecture so that others might learn from their experiences. In the process of preparing for that lecture, using little more than the equipment in their bike shop, they made a wind tunnel and more-or-less founded the science of aerodynamics, correcting formulas that had stood for 150 years.

Armed with a new understanding of lift and wing design their 1902 glider was a success, and paved the way to scale it up, add a power source and space for a pilot, and build the 1903 Flyer. Building the power source was an incredible achievement in itself. Using the new science of aluminum casting the brothers cast their own engine block and, together with their assistant Charlie Taylor, produced a lightweight internal combustion engine with unprecedented power-to-weight ratio, and did most of it in two months.

In December 1903 they succeeded in the first powered, controlled, heavier-than-air human flight, and with the confidence they gained flying over the relatively safe landing surface in the dunes at Kitty Hawk (remember – fail safe!), they returned to Ohio and improved their craft over the next two years until they could sustain flights of over 30 minutes. Without the failures they would never have learned what was needed to succeed.

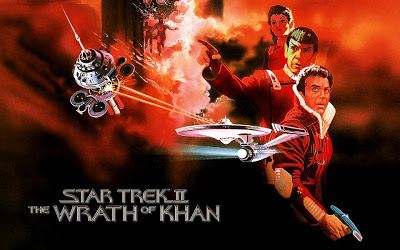

2) Start Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan

The release of the first Star Trek movie in 1979 revealed that there was strong appetite for movies based on the Star Trek TV series, but the movie itself was weak and poorly reviewed. It was successful commercially but everyone knew that Star Trek was capable of greater things.

The first cut of the script for the second movie included Khan as the villain (who featured in an original Star Trek TV episode) and introduced the idea of Kirk’s wife (also from the TV series) and son, but otherwise the plot was very different. In the second draft Spock is killed very early, and Khan gets control of a weapon of mass destruction, which (in the next draft) became the Genesis device, a weapon of mass creation! The next draft moved Spock’s death later in the movie but added the Kobayashi Maru test, and then a whole new draft took out Khan altogether. At this point the writing process looked like a failure.

By this time Nicholas Meyer had been lined-up as Director, but with deadlines looming the producers were still embarrassed about the state of the script. At this point Meyer, with little previous knowledge of Star Trek, rewrote the whole script in 12 days taking the best ideas from the five drafts available and delivered and directed one of the most outstanding science fiction movies ever. Without the previous failures he wouldn’t have had the ideas to work from.

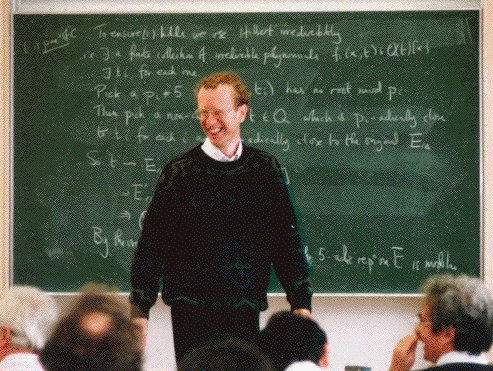

3. Sir Andrew Wiles and Fermat’s Last Theorem

In June 1993 Andrew Wiles presented his solution to one of mathematics’ most famous unsolved problems – Fermat’s last theorem. Every great mathematician had attempted a traditional proof of this easily-stated problem, first posed in 1637, and all had failed. In the 1960s another unproved theory (now known as the Modularity Theorem) was proposed, and in the 1980s it was shown that – if it was true – then the Fermat’s Last Theorem would also be solved. Andrew Wiles had been fascinated by Fermat’s Last Theorem since he was a child and in 1986 he dedicated all his research time to working on enough of the Modularity Theorem to solve this age-old riddle. Working in almost complete isolation by early 1993 he was close enough to check his work with a colleague and then presented what he believed to be a complete proof in June 1993 in Cambridge, England.

Unfortunately, in the process of verifying the proof it became clear that it was flawed, and after months of stressful work in the world’s spotlight trying to fix it Wiles was willing to admit defeat and call his attempt a failure. Much like the Wright brothers, he then decided to at least understand why his attempt had failed so that others might learn from his efforts and take the work further. He emotionally describes how in September of 1994 he had the greatest moment of his working life when he had a sudden revelation related to an approach he had abandoned in 1991, and why a variation of that failed attempt was actually the missing link. In 1995 the “the proof of the century” was published, and it led onto many other breakthroughs in mathematics, none of which would have happened without the earlier failures.

BTW, I recommend the complete documentary and book.

Wrapping Up

In summary I will simply leave you with the words of Thomas Edison: “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Keep trying.